There are times when fate knocks you down to your knees, when it’s hard just to draw your next breath. This happens with the big, bad events in our lives, when we hit losses that define us forever. Sometimes. a single event hits several people at once and the world tends to take notice, though never for long. But what happens once the funerals finish and the reporters leave to chase another story? Do the survivors continue to navigate the aftermath with a “stiff upper lip” or do they tumble headlong through the devastation? Hannah Pittard wants to know.

The Crash

Hannah looks at this question through the lens of one of the sadder stories I know. In June of 1963, a plane crashed near the Orly airport of France, and exploded into a gigantic fireball. 106 of the 122 passengers that died in that inferno were members of the fledgling Atlanta Art Association. Atlanta, in those days was still a fairly small city and those members all came from the same small, tight-knit group: the wealthy, well-born, educated, white, clique that wielded much of the town’s political clout. Their deaths tore a hole in the town’s wealthiest neighborhood and the downtown power structure.

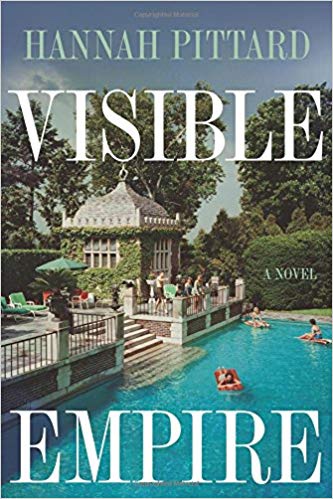

In Visible Empire,Pittard charts the immediate aftermath of the crash mixing real-life with fictional characters. There are those that assume the mantle of duty at once, like the exhausted, nearly noble, Irwin Allen Jr. His mayoral responsibilities force him to compartmentalize his grief while identifying and burying his friends. There’s the fictional (I hope) Southern playboy who celebrates the deaths of his parents by squandering the assets they left him. Little lies and big ones come to light with the crash extending the range of devastation. And into all of this insanity comes a quiet meditation on race.

Atlanta’s Concurrent Tragedy

Although Mayor Allen, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, and their allies were working to desegregate Atlanta, it was still a City of the South, with a tortured racial history. Pittard compares the reverence for air-crash casualties to the denial and obscurity that follows victims of lynchings. Unlike the white, moneyed bereaved, Atlanta’s black citizens don’t have the luxury of falling apart, although one character tries. It is his journey, far from the plane crash of Orly that leads the second half of the novel.

There is much of the Orly tragedy I wish Pittard had written about; how the crash added a moral imperative to constructing the city’s Fine Arts Center; how a daughter in France learned of her mother’s death through a transatlantic phone call; how families assembled and reassembled their lives without the aid of professionals or support groups. But that will be the work of some other novelist. In the meantime, we have Visible Empire to remind us that all life is precious and the future uncertain.

No Comments

Comments are closed.