Sorry if you’ve missed updates of this blog for the past week or two. The combination of seasonal affective depression, a back injury and poison oak knocked me out for a bit. Hope you enjoy the return!

Civilization’s changed a lot in the last hundred years. (That’s an understatement, wouldn’t you say?) We’ve gone from flimsy, barely airborne planes to walking on the moon and probes exploring the solar system; wooden wall phones for the well-to-do to computer smartphones attached to practically everyone; tiny circles of close friends and family to global communities. With all of that change, a lot of formerly private life have become increasingly public. I’m not sure if Elizabeth MacKintosh would have liked the world today. As a mystery writer, she was better than average, but the best enigma she ever created was her life.

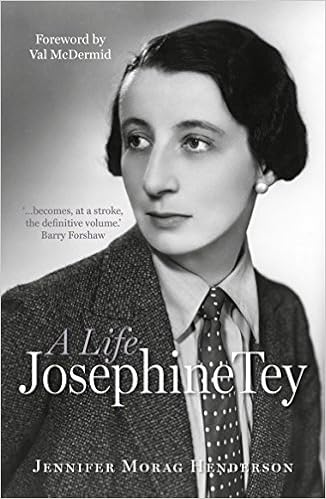

You say you’ve never heard of Elizabeth MacKintosh? Tell you the truth, I hadn’t much either until I ran into J. M Henderson’s Josephine Tey: A Life. And that is the name mystery lovers recognize. Josephine Tey, the creator of the Alan Grant mysteries and Brat Farrar. The lady who entertained us by breaking the rules laid out by other mystery writers. The author who included insights into girls colleges and “the life theatrical” in some of her books but never explained how she got the knowledge. The answer is, they came from other, undisclosed parts of her life.

As Elizabeth MacKintosh, she trained at a girl’s college and taught in England until her mother’s death and her sisters’ marriages returned her to Scotland. To Inverness, she remained ever after Miss MacKintosh, her father’s housekeeper and one of those women who lost a sweetheart in “The War.” Under this cover, Elizabeth began to publish under the name Gordon Daviot: first stories, then plays.

In Miss Pym Disposes, the title character has accidentally become a best-selling authoress. Gordon Daviot’s hit play, Richard of Bordeaux brought the same level of success and consternation to its author. The money from it paid for the occasional bit independence from Scotland and her father’s home, but now Gordon Daviot was supposed to be a writer of historical plays. So Gordon continued to write for the stage, a dozen plays over the next quarter century. And with a new pseudonym, Josephine Tey began to publish well-known mysteries at the same time.

How compartmentalized did Elizabeth MacKintosh’s life get? During the last year of her life, she was terribly ill but never released the news. Her death came as a shock to the celebrated actors who didn’t know “Gordon” was sick, and the Josephine Tey fans who (at least) got one more “Alan Grant” story: The Singing Sands, found in her papers and published posthumously.

Henderson’s biography helps flesh out some of the details hinted at in her subject’s work and the research adds some sorely needed context, but in the end, we only learn what Miss MacKintosh experienced during her life, not what she thought or how she felt about it. Those impressions were not available to the public under any name. They remain the private property of Elizabeth MacKintosh / Gordon Daviot / Josephine Tey. And maybe, that’s as it should be.

No Comments

Comments are closed.